Life and Death after Birth in Alexander de Cadenet’s Inversions and Poetry

- Alexander de Cadenet

- Nov 3, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 14, 2018

By Richard Dyer,

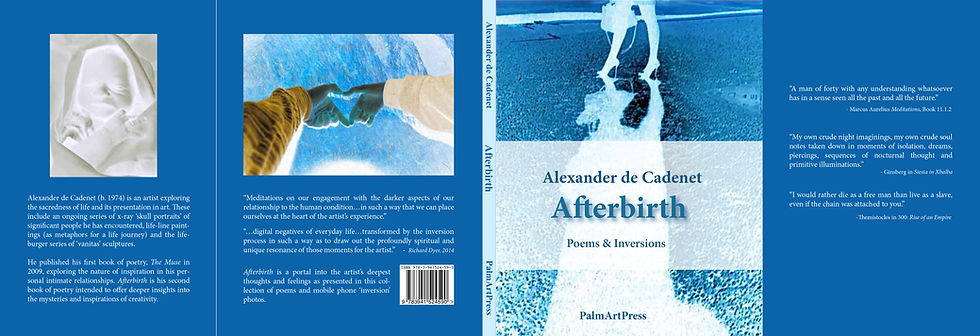

In his first collection of poetry, The Muse, published in 2009,1 Alexander de Cadenet chronicled the emotional and spiritual repercussions of the dissolution of an intense and mutually obsessive relationship. The writing – as in the present collection – is particularly focused through the lens of raw personal experience, unmediated by notions of political correctness or propriety, yet at the same time mines deep seams of unconscious and collective experience. This ability to make the personal universal, the private public and the secrets of inner experience – revealed through subtle articulations of language – makes these nuanced meditations on our engagement with the darker aspects of our relationship to the human condition available the reader in such a way that we can place ourselves at the heart of the artist’s experience.

When that dissolving relationship, unexpectedly, resulted in the birth of his daughter, everything changed. It is known that the actual, physical structure of the human brain is irreversibly changed when an individual becomes a parent. This is evident in the content of the poems in the current collection which now address the radically transformed psyche of de Cadenet as ‘The Father’ and his new and relationship to the mother of their child and their daughter. The title of the collection, Afterbirth, references the literal afterbirth of the placenta, that which nourished the embryo throughout its term and which is expelled after the birth, and at the same time the transformation of the artist’s life and feeling after (the) birth of his daughter in 2013. The problematic and at the same time ecstatic relationship to the female as portrayed in The Muse is here extended and enriched by the entrance of a new life into the emotional arena.

The new poems are presented here in relation to an ongoing series of ‘Inversions’,2 digital negatives of everyday life, which have been transformed by the inversion process in such a way as to draw out the profoundly spiritual and unique resonance of those moments for the artist. This way of working, in the ‘shadow-world’ has its historical antecedents in the ‘rayographs’ and ‘photograms’ of the photographer Man Ray, closely associated with the Dada and Surrealist movements, who placed objects directly onto the photographic paper; Robert Rauschenburg’s Booster (1967);3 and most particularly many works by the British Pop artist Richard Hamilton (see My Marilyn [Past Up], 1964,4 and especially I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas, (1967).5

De Cadenet’s ‘Inversions’ focus on very particular moments from his life – representative here of anyone’s life – those moments when one suddenly becomes aware of the ineffable nature of existence, the universe, and our small place in it. The most ordinary occurrence – a bird alighting on a wire; a glimpse of one’s grandfather through a half-open door, laying on a daybed in another room, moving towards the moment of his death; a swaddled baby at the beginning of theirs – his daughter? Sunrise; revellers partying until the dawn, moving as one. These moments of realisation can catapult one into an altered state of consciousness where, in a moment of supreme clarity, one suddenly sees ‘through the wall’, experiencing the moment without words, without thought, as if one had lived ones whole life behind a semi-opaque screen which has suddenly been lifted, revealing the essence behind; the ‘code’ behind the matrix.6

By inverting the colour and tone of the images, in effect turning them into colour negatives, these moments are transformed into an other-worldly realm, a parallel universe of experience, light becomes darkness and darkness is transformed into light. In his first series of photographs, presented in the exhibition and publication Demi-Monde (2009),7 the artist used that most humble of technologies, the low-resolution digital camera found on any cheap mobile phone, to uncover the hidden secrets of the urban cityscape at night. He employed a different sort of ‘inversion’ in that earlier work, casting what would normally be the principal subject of an image in deep shadow, or only partially lit, and subjecting what would conventionally be the background to the highest saturation of light. In the current series of ‘Inversions’ the artist again explores the power of light to function as a trope for revelation and enlightenment, and of darkness to move us towards a contemplation of the hidden aspects of the world, and our own psyche.

The ‘Inversions’ function as icons for meditative contemplation on the fundamental subjects of life, death and the nature of existence and reality. The subtle colour spectrum, etiolated as if by the overwhelming light of illumination, serves to partially obscure the specific details, thus universalising the images and making them available as an arena for any viewer to project into them their own memories and experiences. The technique, by digitally eliding the specific details of the subject, camouflaging the specificity of their particular existence, transforms them into iconic and universal ciphers for of the human condition, the figures presented like the auric imprint of a Kirlian photograph.8

As with de Cadenet’s long established series of ‘Skull Portraits’, begun in 1996, where he has deployed an X-ray machine to render the inner bone structure of the sitter, the process of inversion masks the identity of the sitter, what remains are literally the ‘bare bones’ of the individual. The skull portraits function in direct dialogue with the inversions, counter-pointing the life-affirming ecstasy of the lucid moment with the inevitably fact of our own mortality. The specificity of the sitter is literally ‘stripped away’ by the unforgiving scalpel of the x-ray machine, revealing the skull which lies within, universal, unchanging. No matter what attributes of wealth and status adorn the outer body, within we are all the same; often all that remains of the life lived are these signifiers of wealth – a Rolex watch, an expensive fountain pen – wealth which will not accompany the owner in the next state. These potent ‘memento mori’ function as stark reminders of our unavoidable fate. What will remain, what survives death is perhaps not the soul but art itself. These works, produced with pigment fused to aluminium panels, will survive long after the demise of the sitters – and indeed the artist – an enduring testament to the Latin aphorism ‘arse longa, vita brevis’, (art is long, life is short).9

However, in the ‘Inversions’ there is embedded the notion of redemption, that out of the darkness will come light, that after the end there is a new beginning. They serve as a shimmering polychrome mirror to the skull portraits, a spiritual riposte, a testament to the eternal return of the human spirit, the transcendent achieved through the everyday.

Richard Dyer © 2014

Richard Dyer is an editor at Third Text, Art Editor of Wasafiri, and a Corresponding Editor for Ambit. He was News Editor and London Correspondent for Contemporary magazine for nearly ten years. He is a widely published art critic, reviewer, poet, fiction writer, practicing artist and a long-standing member of AICA (International Association of Art Critics); he gave the opening keynote speech at the 45th AICA Congress at the University of Zurich in July 2012. His critical writing has appeared in Third Text, Contemporary, Frieze, Flash Art, Art Review, Art Press, The Independent, The Guardian, Time Out and many other publications and catalogues. His latest publications are a chapter, ‘Alpha Beta’, in Magne Furuholmen: In Transit (Forlaget Press, Oslo, 2013); Ben Turnbull: Truth Justice and the American Way (The Peter Scott Gallery, Lancaster University, 2012) and a chapter in Identities/Identiteetit, ‘On the Construction of an Artistic Identity through Diverse Practice’, (Royal Academy Publications, 2012). His major monograph Making the (In)visible in the Work of Mark Francis (Lund Humphries) was published in 2008.

References:

1 Alexander de Cadenet, The Muse, Decadenetworld, London, 2009; www.decadenetworld.com

2 ‘Inversions’, the title of the series, is derived from the digital era name for what used to be termed a negative in photographic language, where all darks become light and vis-a-versa, and all colours become their complimentary, red to green, blue to orange, etc.

3 Robert Rauschenburg, (1925–2008), Booster, 1967, from the ‘Booster and 7 Studies’ series, colour lithograph and screenprint, 183 x 89 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 1973.

4 Richard Hamilton, (1922–2011), My Marilyn (Past Up), 1965, screenprint on paper, 51.8 x 63.2 cm, Tate, presented by Rose and Cris Prater through the institute of Contemporary Prints, 1975.

5 Richard Hamilton, I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas, 1967, screenprint on paper, frame: 89 x 114.2 cm, Tate, presented by Tate Members, 2010.

6 The Matrix, Andy and Larry Wachowski, Directors, 1999. Humans are immersed in a computer generated reality to keep them passive while their unconscious bodies are being used by a race of computer machines as a source of energy.

7 ‘Alexander de Cadenet: Demi-Monde’, The Hastings Trust, Hastings, East Sussex, 5 December 2009 – 4 February 2010; publication, Alexander de Cadenet, Demi-Monde, The Hastings Trust, 2010, 72 pages, ISBN: 0956402011, 9780956402011.

8 Kirlian photography is a type of photogram made with a high voltage plate behind the photographic paper, it is named after Semyon Kirlian who accidentally discovered the process in 1939, it gave photographed objects a brilliantly coloured aura.

9 The original aphorism is by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, and first appeared as the first two lines in his Aphorismi, ‘Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.’ (The Latin translation reverses the order of words).

Comments